August 31st was the longest day of my life. I woke up at 4 o’clock on Friday morning in Christchurch, New Zealand, crossed the International Date Line on the longest of my four flights, sat on a runway in Colorado Springs for 4 hours, then wound up stuck in Denver on Friday evening. After a spontaneous visit with cousins in Boulder, two more flights finally returned me to Springfield on Saturday night. This gauntlet of a journey has given me plenty of time to reflect about the trip, and boy, was it one for the ages. Two weeks of high adventure touring in a place known for its extreme sports and remarkable variety of scenery, from snow-covered mountains to magnificent coastlines to unique volcanic and geothermal features. Fasten your seat belt low and tight across your hips, and I’ll try my best to take you along for the ride.

North Island

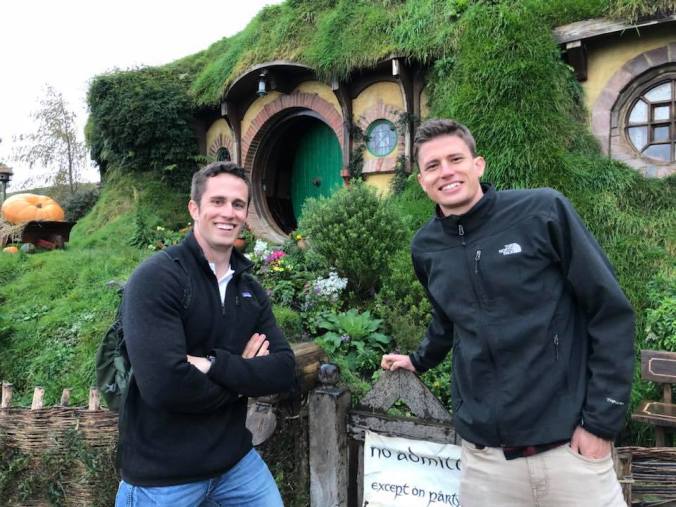

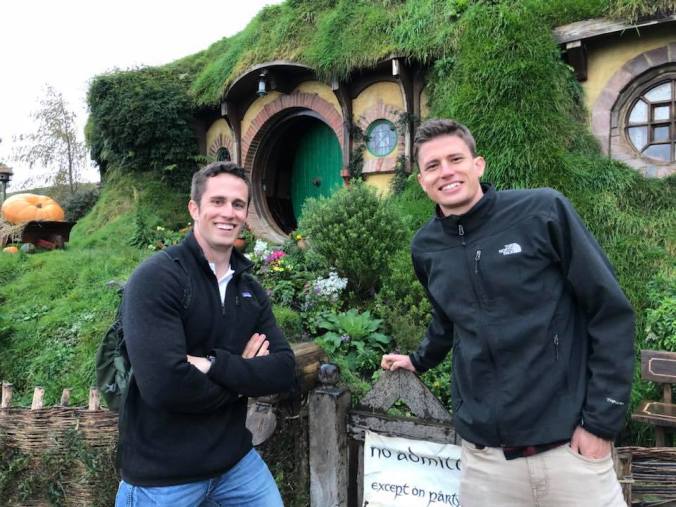

Clayton and I started our journey in Auckland, New Zealand’s largest urban center. Heavy rain prevented us from taking a ferry out to one of the nearby volcanic islands, but we saw the Maori art (from fascinating 19th century portraiture to eclectic modern works) at the Auckland Art Gallery and absorbed the Seattle-like vibe of the downtown harbor. We then set off in our rental car for the North Island countryside, which was both pastoral and rugged, an inspiration for Middle Earth in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. In fact, the first place we visited was Hobbitton, the actual movie set in The Shire. Clayton, a more avid LotR fan than I, was positively brimming with childhood excitement as our hobbit-like guide Dan led us around the 40 or so meticulously landscaped hobbit holes constructed for filming. My excitement was tapped too as we partook in the evening feast, a smorgasbord of woodfired meats, vegetables, New Zealand desserts, cider and ale served on long tables at the Green Dragon. Honestly, the whole experience was otherworldly, it was very easy to imagine we were in the Shire that night.

We had some ‘party business’ at the Hobbitton movie set.

The next day, we participated in a wild caving tour of the Waitomo glowworm caves with the Legendary Blackwater Rafting Company. The adventure began with a 120-foot abseil (cooler version of ‘rappel’ used in NZ) down a narrow limestone shaft. A short zipline then flung us through a chamber with hundreds of glowworms, like stationary stars dotting the cave walls and ceiling. Unique to New Zealand, these glowworms are the larval form of the fungus gnat, but it’s way cooler to gaze at their starry patterns than to think about their biology. Grabbing an innertube, we proceeded to jump off a ledge into the frigid water. The blackwater rafting portion of the trip was a gentle float along a subterranean stream with hundreds of glowworms up above. At one point, our guide yelled some incantations in Maori and loudly slapped the water; this disturbance provoked the glowworms to luminesce several times brighter, an instinct to attract insect prey. Under the light of a thousand glowworms, our guide waxed poetically about his spiritual connection to the cave, ascertaining the meaning of life – you just had to be there. We floated over a couple of rapids and a short waterslide before free-climbing two 12-foot waterfalls to ascend back into the New Zealand rainforest. Spectacular and very New Zealand experience overall!

Abseiling into the Waitomo cave system.

That afternoon, we stopped by the Otorohanga Kiwi Centre, a top-tier conservation facility for brown kiwi, the most common yet still endangered kiwi species endemic to the North Island. Kiwi can only be observed in pitch-dark nocturnal exhibits, and it was cool to see the strange bird running on its stout sticks of legs and digging for food with its spear of a beak. Several other bird species unique to New Zealand were on display as well, including kea, kaka, kakariki, several varieties of teal, wood pigeon, and oystercatcher; a highlight was watching the oystercatcher pick up a mussel, crack it open against a rock, and toss back the meat, all within about 15 seconds. The freshwater eels were numerous, lifting their heads out of the water to feed on a mixture of meats. We also saw a tuatara, a large, iguana-like reptile older than many dinosaur species that has only survived in New Zealand.

Our next stop at the Hamilton Gardens was surprisingly a trip highlight…arriving 20 minutes til close, Clayton and I ran through the maze of intricately designed meditation spaces. There were surprises at every corner: an Italian courtyard designed to Medici blueprints, an English tudor garden with a distinct Alice-in-Wonderland feel, a Maori farming terrace centered around an ornate food storage tower, a tropical oasis, a larger than life sculpture garden, and more…never have I had so much fun in a botanical garden with someone my age. Hamilton proper was a pretty cool city, and we splurged on beer and salted oysters in a trendy nosh spot downtown before capping off our evening with a drive through the Waikato plains under a vast starry sky.

Maori-style kumara plot at Hamilton Gardens

The next day, we woke up for a Pacific sunrise on Hahei Beach before walking the scenic path to Cathedral Cove. The Coromandel Peninsula is one of the most beautiful areas on the North Island, and we were treated to a series of desktop-background views. Arriving to the secluded cove at high tide, we heard the waves thundering as they broke in the cathedral-like natural archway, steadily carving away at the towering limestone walls. On the other end of the beach, a cold spring waterfall trickled out of the canopied clifftop 50 feet above. I could have sat in the soft white sand all day, taking in the views of Sphinx Rock and the surrounding striated bluffs. Instead, I dove into the icy clear water and breathlessly swam into two limestone caves, where I was completely alone with my echo and a small strip of sand. An incredibly peaceful place to spend a warm spring morning.

High tide at Cathedral Cove didn’t stop me from walking beyond the magnificent archway.

Just 5 miles down the road, we stopped at Hot Water Beach. As the name suggests, digging in the sand in certain spots reveals geothermally heated pools of water, ranging from lukewarm to downright scalding. Clayton and I rented a shovel in town and got to work on our ambitious earth-moving project: a spacious beach-jacuzzi with the perfect natural water temperature. We staked out a spot on the border between hot and cold, just a few feet from a steaming stream that was unbearably hot to stand in for more than a second. After a solid 20 minutes of digging, we perfected the temperature by diverting a small channel of this hot stream into the cool side of our pool. Then we sat, relaxed and content, chilling in a large hot bath. When I started feeling overheated, another dip in the ocean was just what the doctor ordered. I left the Coromandel with every nerve and muscle in my body relaxed, completely pruny but rejuvenated.

We spent the night in Tauranga, a peninsular city in the Bay of Plenty. Looming over the city is Mt. Maunganui, a solitary volcano at the end of a sandbar. Though completely deserted on our misty morning stop, the beach is steeped in history, from arguably the most important Maori treaty in 1840 to historic surfing competitions in the 50s and 60s. Tsunami warning information was posted everywhere, instructing visitors to run up the mountain when they feel an earthquake. New Zealand’s position on the Ring of Fire means there is a high risk for seismic/volcanic activity throughout the country, and nowhere was the urgency of this risk more evident. We climbed on the lava rocks, narrowly avoiding the sea spray from natural blowholes. On the way out, we passed through Te Puke, the center of the agricultural belt and kiwifruit capital of New Zealand. Naturally, we had to stop at Te Puke Diner, and we were rewarded with the best meat pies of the entire trip. The power breakfast was important, as our stomachs would soon be tested by some insane whitewater rafting.

Bracing for impact at Tutea Falls, Kaituna River gorge

The Kaituna River is most famous for Tutea Falls, which at a height of 7 meters is the highest commercially rafted waterfall in the world. But the other 13 class-5 rapids combine to make this the most intense, action-packed hour of whitewater you’ll find anywhere. Anticipating the possibility of a flip, we received a “crash course” on how to get down in the ‘brace’ position, including the unusual command to curl up in a ball if we found ourselves in the water (normally you’re supposed to float along with your feet pointed downstream, but the high water volume ensured that the main risk was getting caught in a ferocious eddy). In the brief moments between rapids, I caught some glimpses of the spectacular scenery: fern trees and jungle vines hanging off the sheer brownstone walls of the steep canyon. We nailed the first few rapids, but no amount of forewarning could have prepared me for what happened at Tutea Falls. Clayton and I braced ourselves to the front of the raft as we sailed over the 2-story drop and plummeted into the swirling whitewater below. But rather than completing a graceful dive as planned, the raft reversed course and launched itself straight up the waterfall. While Clayton gently fell over the side of the raft, I was knocked out of the boat by an avalanche of bodies and oars pummeling my head and shoulders. When I tried to surface, I kept bumping against other flailing people and the pontoon: it wouldn’t be a good story if the raft didn’t land on top of me too. That’s when I remembered to ball up, but I kept hitting obstacles on the way up so abandoned that plan immediately. I gulped in two breaths of water before finally surfacing just as the guides were flipping the raft back over. Winded but flush with adrenaline, I climbed in and proceeded to pull in our raftmate Kev, an older Welsh man with a bum knee, while Clayton adjusted his GoPro. I’ll be honest, the experience seemed a bit scary and dangerous to me, but Clayton had a grand time. In the immediate aftermath, our team couldn’t remember how exactly we flipped, but once we pieced it together, it makes for one hell of a war story, right?

We survived! (This is the driest picture of our raft.)

After drying off, outside and in, we continued around the ancient crater lake to the city of Rotorua, the epicenter of Maori culture in New Zealand. We were treated to an extensive introduction to Maori culture at Te Puia, a living museum situated in a steaming geothermal valley. Our tour guide was a distinctively Maori man (with dark hair in a ponytail and sleeve tattoos peeking out from the edges of his jacket) named Paul McGarvey…no joke, like many Maori, he has at least one line tracing back to the British Isles. Anyway, he helped bring the reconstructed tribal village to life as he explained the Maori social customs, detailing strict traditional gender roles; for example, women were forbidden to carve wood because the process of felling a tree was dangerous, digging and burning out the root system until the tree comes crashing down. Thus when we toured the on-site national institutions for traditional carving and weaving, men were demonstrating the various carving arts while women worked on intricate weaving. The evening was capped with a Maori cultural show and hângî: a barbecue feast of lamb, beef, chicken, and native vegetables cooked in an in-ground, geothermal oven. We reenacted a customary greeting with the village leaders (a show of force followed by a conciliatory touch of foreheads) then were treated to a magnificent song and dance performance. After the delicious buffet feast, we learned how to do the haka, the war dance of the Maori. So the next night when we watched New Zealand’s beloved All Blacks annihilate the Australian Wallabies in a rugby match, we recognized every move of the haka, which the All Blacks famously perform pregame to intimidate opponents.

Professional Maori dancer demonstrating the Haka

Rotorua is also New Zealand’s geothermal center, boasting hundreds of hot springs around the Maori sacred ground of Whakarewarewa. Te Puia had its fair share of boiling springs, none more spectacular than the Pohutu geyser, which was actually two geysers. The smaller geyser, nicknamed the ‘indicator’, continuously sprays to a height of a couple feet. As the pressure builds underground, the ‘indicator’ increases in intensity until a 40-meter jet erupts behind it. This steaming fountain of near-boiling water persists for 15 minutes and erupts at least once per hour, so we went back to watch multiple times it was that cool. I could also watch the mud pools for hours, as superheated gas (water vapor plus minerals including sulfur) bubbled up to create regenerating ring patterns, like a pond of self-molding clay. On a rainy day, one of the mud pools was belching gas angrily, shooting globs of mud several feet in the air and obliterating its circular striations. A short drive up the road lies the quieter yet just as steamy Waimangu thermal valley, a hotspot for geothermal features in a rift created by the (geologically recent) eruption of nearby Mt. Tarawera in 1886. Located in a blast crater is the largest hot spring in the world, Frying Pan Lake. Here, steam rose from the 130 °F surface in mesmerizing swirls…it was like watching a miniature weather simulation, and I geeked out as the steam congregated in fronts and occasionally formed mini-tornadoes above the water. The blue pool spring and steaming cliffs were also impressive. We fittingly capped off the day by relaxing at Rotorua’s historic Polynesian Spa, a complex of naturally heated pools built on two hot springs featuring different blends of minerals. Sure my dry skin flaked off and my shorts now irreversibly smell like sulfur, but it felt sooo nice.

These particular mud pools were protected from being mined and sold as sought-after women’s facial products.

Pohutu Geyser, too tall to fit in the frame

Wonder why they call this Frying Pan Lake…

The next few days flew by, with Clayton succumbing to a severe sore throat and exhaustion finally catching up to me after that action-packed first week. The saying that “it’s only fun until someone goes to the hospital” held somewhat true; fortunately, New Zealand’s healthcare system gave Clayton the appropriate care/antibiotics within an hour and we continued on our way. We spent an afternoon in Taupo, stopping by the gushing Huka Falls and taking a relaxing boat cruise on Lake Taupo to see the impressive (but notably modern) Maori rock carvings. Looking to the far side of New Zealand’s largest lake, we could see the majestic snow-capped volcano Mt. Ngauruhoe garnished by a few low clouds in an otherwise clear sky. The sunset across the lake was simply spectacular as well. However, these would be our only views of the volcanoes within Tongariro National Park, as the next day was a complete washout. Our guided trek of the famous Tongariro Alpine Crossing was canceled for the rain, and I instead hiked alone through lava flows and alpine marshes. Normally, I would have seen 3 large volcanoes looming over the trail, but the dense fog and driving rain convinced me I’ll need to come back during better weather. We pressed on to Wellington, New Zealand’s capital with big-city entertainment and a small-city feel.

The Weta folks made this wonderful piece of public art for the Wellington airport.

Tucked in one of Wellington’s hilly neighborhoods is the Weta Cave, an internationally acclaimed studio for special effects. They’ve had their hands in a number of blockbuster movies, and the workshop is packed full of costumes, props, and scale models of characters (some smaller and even some much larger than life) used in past films. Our tour guide was a chain-mail specialist, which means he spends his days linking rings of steel or leather to create armor for movie stars to wear on set. Pretty unique job. While the Lord of the Rings creations steal the show, I was particularly impressed with their materials and robotics section; in this day and age, seemingly any texture or effect can be created using advanced polymers and robotically driven movements. We also visited New Zealand’s national museum Te Papa and the botanical garden/space observatory. Finally, we treated ourselves to a few great meals of Asian food, headlined by my guy Steven Adams’s favorite Malaysian noodle place. Our enjoyable day in Wellington was a nice way to get our legs under us before our flight to the South Island, where taller mountains and even higher adventure would await.

South Island

We began the second half of our journey in Dunedin (pronounced dun-EE-din), an industrial city on the south Pacific coast known for Cadbury chocolate and Speights beer (we had plenty of both!). Our first stop was Baldwin Street, recognized by Guinness as the world’s steepest street at a slope of 2.86:1. Not trusting our economy rental car, we walked up the 1/4 mile hill, and was it steep! The sidewalk was literally a staircase. The houses were obviously built on a level foundation, but the slope created some pretty funny illusions of tilted buildings. We ate lunch on the Octagon — as the capital of Otago, Dunedin’s city center was cleverly designed on an octagonal street layout. Then we spent the afternoon on the Otago peninsula, an incredibly beautiful countryside with steep pastured hills and vistas of both the harbor and the open ocean from Highcliff Road. Our main stop was at Allan’s Beach, a secluded beach accessible by a one-lane dirt road hovering precariously over the bay (driving it felt like I was in a car commercial) then stepping over two fences to cross a private pasture. Clayton nearly stepped on a sea lion, the highlight of our mostly futile search for wildlife. Turns out it was all just farther along the peninsula…

Standing at the top of the world’s steepest street like it’s no big deal

As evening approached, we visited the Royal Albatross Centre, a conservation facility around the only mainland breeding colony for albatross. There was no shortage of shorebirds surrounding the cliffs, as I counted 3 albatross soaring high above the clutter of gulls. When night fell, we took a guided walk down to an illuminated viewing platform to watch the blue penguins, the smallest penguin species in the world. Twenty minutes of waiting in the cold wind for pitch darkness, then a ‘raft’ of over 30 penguins arrived on the beach. Communicating with one another through audible ‘qwok’ vocalizations, they waddled as one mass up to the rocks, where they clambered clumsily over each other to their nesting burrows. Soon, trills of happiness echoed around the bay from mating pairs thrilled to be reunited: after all, penguins can spend weeks at a time fishing in the open ocean. A few stragglers later arrived on the beach, in much less of a hurry to get home–these were likely bachelor penguins, shooting the breeze and surfing the waves like they had nowhere to be. It was really fascinating to see penguin social dynamics, particularly the anthropomorphism of a daily commute (with order and communication) returning to a monogamous household. Especially knowing that conservation efforts on that particular beach make it all possible.

March of the little blue penguins

The next day we drove across the island to Te Anau (via Gore, the country music capital of New Zealand, who’d’a thunk…), our gateway to Fiordland National Park and the Southern Alps. There we hiked the Rainbow Reach track, which features key settings from Lord of the Rings and the Two Towers. Though I didn’t really remember the movie, I knew immediately when we entered Fangorn Forest, as the mossy trees and billowy ferns looked very Middle Earth. Also, orcs kept popping out, it was weird. Anyway, we continued to the Gladden Fields, a wide fen with a fantastic echo where we could hear our voices bounce in a triangle off of the mountains. The end of the trail coincided with the end of the movie, where we stood on a gravel beach looking off at a fiord at the far end of Lake Manapouri. With that, I can say that I don’t need a Lord of the Rings marathon, because I walked one! We finished the day with pizza and beer in town, serenaded by a country-western (or reeeeally southern?) cover band. Say what you want, I thought they were really good!

One of the temperate rainforests of Middle Earth

We set off for Milford Sound early in the morning, just as the clouds gave way to a beautiful clear sky. Even the cop who nabbed Clayton for speeding (13 kph over the limit on the only straight road we drove all day, mind you) couldn’t put a damper on how great this day was. The 360° panoramas from the alpine meadows in Eglinton Valley were just awe-inspiring. The sky was completely cloudless during our cruise on the Sound, a rare occurrence in a place that receives 7 meters of rain annually. The boat ride took us beneath the cliffs, which were hundreds of feet tall and dotted with dangly fern trees. I learned that Milford Sound was Rudyard Kipling’s inspiration for the Jungle Book, which was hard to picture considering the snowy peaks that stretched above the green-brown cliffs. But imagining the usual rainy conditions, the cliffs would disappear into dense low clouds, giving the illusion that the waterfalls continued infinitely into the sky and that the Sound is walled in by jungle. We saw brown fur seals sunning on ‘seal rock’ and a yellow-headed Fiordland crested penguin swimming circles in a quiet inlet. The return voyage gave us a long look at the majestic Mitre Peak, cementing how incredibly lucky we were to have such ideal weather. On the way back, we hiked Key Summit, where once we climbed past the treeline, we were treated to a spectacular 360° vista of as many snow-covered mountaintops as we saw on our entire week-long trek in Peru. We finished the drive to Queenstown after sundown, but fortunately the moon illuminated the snowcaps on the surrounding mountains — the views were just as surreal at night, somehow. It was a day full of indescribable, you-just-had-to-be-there views…New Zealand at its absolute finest.

Mitre Peak towering over Milford Sound on a beautiful day

Key Summit, no description needed

Queenstown was our base camp for skiing, as we spent the weekend on the slopes of Mt. Cardrona. Now, I hadn’t been downhill skiing since I was 8, so there was a steep learning curve. For one thing, they let me use poles this time, which was essential with my balance having fallen off some. As the least experienced among my adult beginners class, I had to use my poles to fake like I knew how to stop and steer at first. 3 runs on the green (beginner level) slope later, I was confidently cutting my lines by lunchtime, albeit slowly. But it’s not a ski trip — and certainly not a trip with Clayton — without some “Oh $#&%!” moments, and I got some when Clayton took me out on an “easy blue run” after lunch. I stopped in my tracks at the top: this slope was steeper than Baldwin Street and booby-trapped with moguls (because it was actually an advanced run…oops). Clayton went over first, but his skis immediately fell off. Thinking I could help him reattach, I inched my way toward his position in the middle of the steepest area. Before I made it, he ran off on foot in frustration (turns out he had mistakenly grabbed someone else’s skis after lunch, but he was ready to go full attorney on whoever tampered with his pair), leaving me stranded on what felt like a sheer cliff. I ended up inching down on my butt, falling a few times, then rejoining my lesson with a renewed sense of humility for the rest of the afternoon. But hey, by the end of the second day, I was carving up the intermediate blue slopes like they do in the Olympics — at least that’s how it felt, skiing is exhilarating. Clayton and I took turns filming each other with the GoPro, nabbing first-person footage of the two best runs of the day. I must say, Cardrona has some really good skiing, especially for August!

Look at those snowfields! The skiing was terrific at Cardrona.

Clayton had been anxiously anticipating our nights in Queenstown, and the town delivered. The legendary Fergburger lived up to its billing and then some: I wasn’t expecting a burger from a tourist town in New Zealand (a venison burger with caramelized onion and boysenberry compote, to be exact) to be possibly the best burger I’ve ever had. We also had a [situationally perfect] meal of pizza and beer at The Cow, an old stone milking shed converted into a rustic tavern. Queenstown is better known as a mecca for adrenaline sports, so we made a stop at the AJ Hackett bungy center on the historic Kawarau Bridge. Since being the first in the world to commercialize bungy jumping at that very spot in 1988, adrenaline junkie AJ Hackett has become famous worldwide for enabling over a million people to bungy jump. Not to be outdone or left out, Clayton added his name to that list — after signing away his life, they wrapped a bath towel around his ankles, secured him with a harness and three lifelines to the big bungee, and told him to jump off the bridge. My friend swan-dived into a 5 second free-fall, grazed his head and arms against the river below, bounced around like a yo-yo for another 30 seconds, then was untied by the crew in a raft below before all his blood rushed to his brain. While watching it confirmed that bungy jumping is not a sport for me, it also reassured me that the structural engineering of the bungy connection is well-reasoned and highly safe, having seen the series of pre-flight tightenings and checks firsthand.

I did get a taste of the free-fall at our next destination, as we went skydiving in Wanaka (rhymes with Hannukah). The fear didn’t hit me until I read the waiver that explicitly outlines the “risk of being killed” should the parachute malfunction, they didn’t sugarcoat it at all. But I was encouraged that the man who would be strapped to my back, a big Maori guy named Apiate, has worked in skydiving for 8 years. Liking my chances, I put on my orange jumpsuit and harness then was loaded into a small plane with no seats, only two rubber beams to queue up the jetsam. The anticipation built as we rose in our unpressurized cabin above the surrounding mountaintops — everyone had to work to suppress their nerves and their gas. When they yanked open the door, Apiate and I were immediately on deck. I couldn’t have backed out even if I wanted to, since Apiate was the one who launched us out into the sky, followed by a cameraman. We did one somersault then righted so I was face down, 12,000 feet above the ground and dropping like a rock. The free-fall was insane: you reach your terminal velocity of 100+ mph within seconds, and it feels uncontrollably fast. Then, you get used to it and the speed becomes a thrill. Then, you pass through a barrage of baby ice crystals trying to form clouds and realize your cheeks skipped over being cold to becoming numb. Before you know it, your guide pulls the chute. This was the best part, soaring like a bird over the beautiful mountain valley that I didn’t have the wherewithal to soak in during the free-fall. He even let me steer for a couple of minutes, which was just surreal. When it was time to land, Apiate maneuvered our chute so that it set me down like a baby onto the soft grass. I don’t want to try my luck with another jump anytime soon, but my first skydive was an incredible rush, and felt surprisingly safe!

Taking aim at the hole in the clouds from 12,000 feet

After a series of clear days, we were due for some rain. We snapped photos with the iconic Wanaka tree, a rickety willow standing alone in the cold lake. We enjoyed the mind-bending illusion rooms at Puzzling World, where even my science-wired brain was impressed with some of the effects. I went mountain biking in the Sticky Forest, a hillside pine grove with a vast selection of (mostly difficult) downhill bike trails. We skipped rocks on the shore of Lake Hawea, where every stone was round and flat. We drove through Mount Aspiring National Park, whose ranges of snowy mountains viewed across expansive lakes and glacial valleys provided some of the best scenery of the entire trip. We hiked to the base of Fox Glacier along a valley that was ice-covered until recently, walking about a mile from where the glacier ended around 1960 to a viewpoint that had been under ice until at least 2008. We stopped at a rocky beach on the Tasman Sea, with a backdrop of pine forests and snowy mountain tops (and sea spray from violent waves) that reminded me of the Pacific Northwest. As night fell, we hiked from our hostel in Franz Josef Glacier up to the Tatare tunnels, an abandoned mine shaft with glowworms inside. We extinguished our lights at the end of the tunnel, revealing a few hundred glowing lights surrounding our heads. Really a unique hike…even the little activities we did on a whim were memorable in their own special way.

Power team exploring the Tatare tunnels at night, feat. glowworms on the ceiling

As a grand finale for the trip, a helicopter dropped us off on top of Franz Josef Glacier for a guided ice hike. I had never ridden in a helicopter before, which was a thrill in itself. I was surprised how far the chopper leans forward when you are flying, which gave us great views of the glacier as we ascended the valley at a low altitude. Once we landed on the ice, we strapped steel crampons onto our boots then set off with trekking poles. Because of the inherent dangers presented by live glaciers (and several tourists in our group who couldn’t understand our guide’s English commands), progress across the ice was slow and measured. Every few minutes, a chunk of the glacier would calve off, clattering down the pile of rock and ice. We trekked around the lowest tier of ice formations, through a small ice cave, and over blue cascades of melt water. The views of ice all around us were definitely the highlight, though, and it was special to know that we were standing on one of the world’s most active glaciers (in terms of calving at the bottom and being replenished by snow fields at the top).

Heli-hiking on Franz Josef Glacier as it rapidly recedes

To finish off our last day in New Zealand, we did one more epic drive through Arthur’s Pass National Park, replete with more unbelievable vistas of the Southern Alps at sunset that served as a sort of sendoff. A late dinner in Christchurch, a city that is still in scaffolding after devastating earthquakes in 2010 and 2011, and it was a wrap. It was truly a trip for the ages. I could spend months traveling New Zealand, between the many backpacking treks over the diverse terrain and the other activities spanning all seasons. In case I never go back, I feel like our two week journey gave us a comprehensive taste of all New Zealand has to offer. That’s part of the fun of traveling: seeing the sights on your itinerary while discovering more exciting aspects that might not have made the guidebook. If I was into comparisons, this adventure would be hard to top…but that’s not the point of traveling, in my opinion. What brings me the most joy is learning about the world, and I hope I was able to convey my experiences in a way that shares that fervor with you.