Last Saturday’s EF4 tornado in Lee County, Alabama marked the strongest tornado in over 2 years, claiming 23 lives on its destructive 70-mile path through multiple states. It was part of an outbreak that is typical for winter/early spring, a region of widespread convective activity at the convergence of a dipping jet stream of cold air with early season moisture from the Gulf of Mexico. This meteorological setup is of particular interest to severe weather researchers, as the low CAPE and minimal CIN of this system buck conventional understanding of tornado formation. But these conditions are frequently observed in tornado outbreaks in the Southeast, which begs the question: if there’s not an abundance of buoyant, warm air exploding into a cold upper atmosphere, what drives the intensification of a devastating tornado?

In short, nobody knows. Meteorologists can predict an enhanced probability for tornadoes based on a regional meteorological context, but they can’t pinpoint whether a particular storm will produce a tornado, even for the strongest long-track tornadoes. I was too busy to run my surface heating model in advance of this outbreak, but there are no definitive topographical heterogeneities in the vast pine forest upwind of this tornado’s damage track. I know that simulated supercells can produce long-track EF5 tornadoes or nothing at all given the same input parameters, so there’s some kind of elusive balance involved within these storms. I’m more hesitant than most meteorologists to chalk anything up to anomaly, but there was certainly anomaly with this system as a second EF2 tornado improbably retraced almost the exact path of the first a mere 30 minutes later…

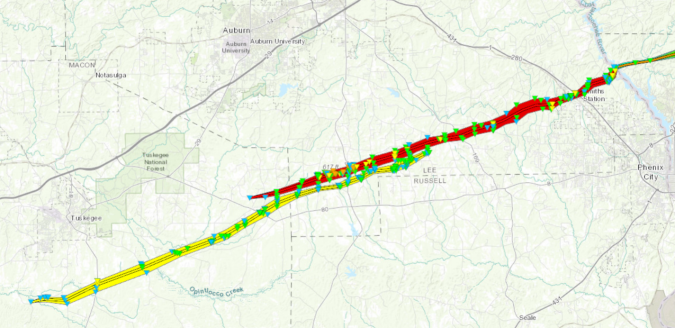

Lee and Macon Counties in Alabama were hit by back-to-back tornadoes on 3/3/19

While my surface heat and moisture model seeks to improve tornado forecasting, we are still far from a catch-all predictor of tornadogenesis. I can’t imagine how terrifying it would be in the path of the first tornado as a second tornado formed minutes behind. But it’s important that these scenarios, even if improbable, are thoroughly covered by NWS warnings: every tornado in this outbreak (and the smaller fatal outbreak in Mississippi on 2/23/19) was preceded by a tornado warning. Even if the warning was only 9 minutes for that EF4, it’s a start as we continue to research the critical signs of tornadogenesis. These tragedies never fail to leave me with a heavy heart, but I acknowledge that science is a years-long process of observing and building understanding – so I’ll keep pushing.